When you protect yourself, you're making a choice for those who can't protect themselves.

In recent years, concern for vaccine safety seems to be getting more attention than the crippling effects of the diseases vaccines are intended to prevent. In turn, more people are hesitant – not completely unwilling, but also not convinced of a vaccine’s value. The World Health Organization listed vaccine hesitancy as a top 10 threat to global health in 2019. With that, it’s important to understand how vaccinations work for the community as a whole.

What Is Herd Immunity?

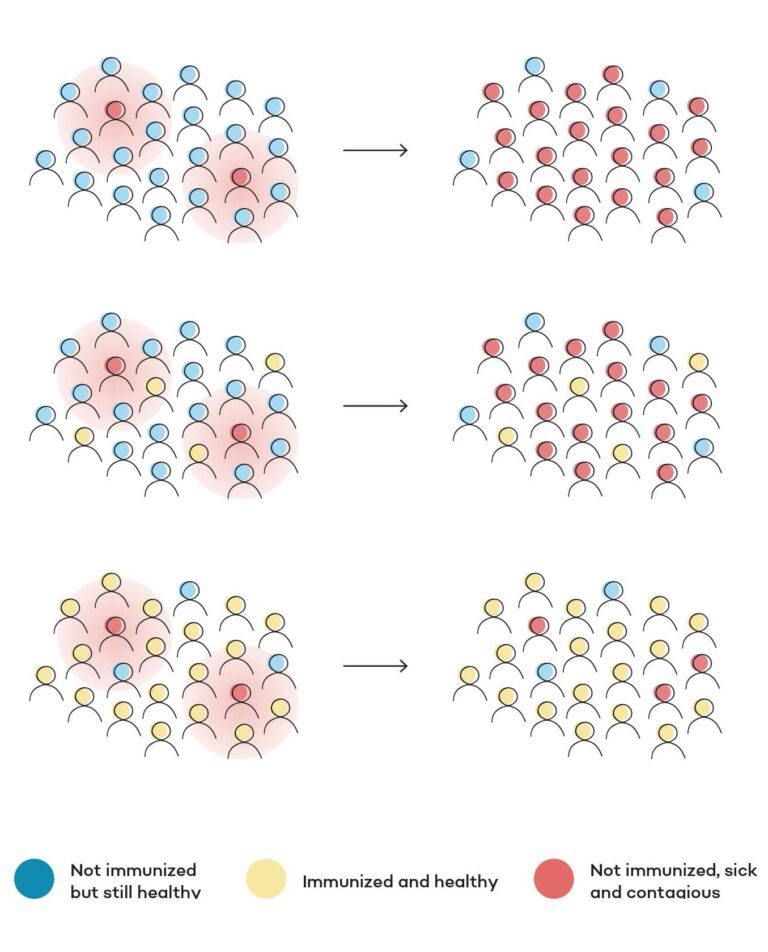

Herd immunity happens when a population limits the person-to-person transmission of a germ responsible for infection, ultimately protecting the community from an outbreak of disease. In simpler terms, it limits a disease’s ability to spread. Also sometimes referred to as “community immunity,” herd immunity is achieved through vaccination.

When a certain percentage of the community is vaccinated against a communicable infectious disease like the flu or measles, the community as a whole becomes less susceptible to outbreak, and individuals within the community who did not vaccinate by choice – or who are ineligible for the vaccine – are protected indirectly. If a community loses herd immunity because not enough individuals have been vaccinated, there’s a greater likelihood of new cases of illness, each member of the community is at a higher risk of being infected, and those unvaccinated go unprotected.

It is important to realize we are eligible to pass illness (or the potential for illness) on to someone else even when we aren’t actively sick. According to the Oxford Vaccine Group, you can be a carrier of a bacteria that could potentially lead to infection and not know it. Meningococcus, for example, is a type of bacteria that many of us carry in our throats already. (It has to make it to the bloodstream in order to become meningitis.) Vaccination prevents you from contracting this illness and spreading it to someone highly susceptible to infection, like an infant, which could be deadly.

Babies cannot receive their first of five vaccinations for pertussis until they are two months old. A painful respiratory illness, pertussis can cause pneumonia, brain damage, or death in an infant. They rely on herd immunity for protection.

Herd Immunity Thresholds

Herd immunity is reached when a specific majority percentage of the population is vaccinated against a specific illness. The vaccination rate needed to achieve herd immunity is different depending on how contagious the illnesses are. Because it is severely contagious, the World Health Organization reports that more than 95% of a community needs vaccination against measles to achieve herd immunity. Similarly, 92-94% of a community needs vaccination against pertussis, more commonly known as whooping cough, to achieve herd immunity. A less contagious disease would require a lower percentage. Polio, for example, only needs an 80-85% vaccination rate and mumps 75-86%.

Because in the United States the devastation of diseases like diphtheria and polio happened before our lifetime, we haven’t developed a fear of just how serious an outbreak can be. “Sometimes people aren’t familiar with how bad a disease really is because it has become so rare, or they may believe that the disease is so rare that the risk is low anyway, so the vaccine isn’t really useful for them,” explains Dr. Eric Betts, a family physician with CHI Memorial Family Practice Associates — Chickamauga & LaFayette. Yet when one person becomes ill in a community that has lost herd immunity, it can mean trouble. In California in 2015, a measles outbreak began when a single unvaccinated child was brought to a hospital with a rash. The disease quickly re-emerged in the area, with 125 cases linked to that child’s recent visit to Disneyland alone.

“Just because a disease has become rare due to immunization doesn’t mean it can’t happen,” explains Dr. Betts. “You may not travel or think you don’t come in contact with anyone. But you have to think of the person you see in the grocery store or church, and who they work with and where they may travel. It isn’t just your immediate family, as diseases can spread in just a few people to reach hundreds then thousands.”

Understanding Vaccines

The immune system fights infection by creating antibodies that go to war against a bacteria, virus, or other microorganism capable of causing disease. As soon as the bacteria, virus, or microorganism enters your body, it attacks and multiplies. White blood cells produce antibodies, swallow up germs, and attack the cells that have already become infected. Your immune system learns how to fight that particular germ, so the next time the pathogen enters your body, your immune system is ready to ward it off.

Today vaccines work by introducing a small partial, weakened, or inactive virus or bacteria to imitate an infection. “Vaccines expose the body to small particles that activate an immune system response to create antibodies,” explains Dr. Courtney Cash, a family physician with AFC Urgent Care — Ooltewah. “That means when it’s exposed in the future, the body can fight off the bacteria and kill it before it’s able to create an infection in that person.”

Side effects from vaccines are typically mild. “Vaccines do not make you sick,” says Dr. Cash. “While you may have a small immune response – like not feeling good for 24 hours – you cannot actually get the infection, which is a common misconception.”

Q: Is every outbreak the result of lost herd immunity?

A: No! It’s not always appropriate to assume vaccine hesitancy (or choosing not to vaccinate at all) is the cause of an outbreak. The journal Science Translational Medicine, for example, recently published that mumps outbreaks over the last 10 years – which have frustrated the goal to eliminate the disease in the United States – are perhaps because the strength of protection wanes in the years after a child has been vaccinated. This is why the MMR vaccine moved to two doses in 1989, and also why it’s still possible to see a disease like mumps resurge in communities of people who have been vaccinated, specifically in young adults at colleges and universities. It’s also possible that a virus like influenza can experience a “genetic drift,” or a change in its make-up that allows it to evade the efficacy of the vaccine over time.

Why Herd Immunity Is Important

Herd immunity protects people who cannot be vaccinated. This includes infants who are too young for a specific vaccine, anyone who has been told by his or her physician that a vaccine is inadvisable due to medical conditions, an elderly individual with a weakened immune system, or anyone whose immune system is compromised. Among other things, a compromised immune system can be caused by undergoing chemotherapy; having an HIV diagnosis; or taking medication after an organ or bone marrow transplant, which helps stop the patient’s immune system from attacking the new organ or marrow.

The bottom line is you’re not just protecting yourself when you choose vaccination. Herd immunity protects those who simply cannot protect themselves. It also helps cover individuals whose vaccination was not successful. Herd immunity contains outbreaks by slowing the rapid spread of disease and protects the most vulnerable.

“Herd immunity doesn’t make it impossible to get an illness – the only way to do that is to eradicate the disease, which is much more difficult. But just because someone gets whooping cough doesn’t mean vaccines failed in general,” explains Dr. Betts. “That person may not have developed enough antibodies so the vaccine didn’t work for them, but think of the greater public and that the whooping cough didn’t keep spreading past those one or two people. That is what herd immunity is for.”

Each time an infection reaches a person who has been vaccinated, it is another “end of the line” moment for a branch of an outbreak. As you decide what is best for you and your family, talk to your doctor about any anxiety or hesitancy you may have about vaccinations. “He or she can help you understand any potential risks or consequences in addition to helping you get a good understanding of what the vaccine is intended for,” says Dr. Cash. You can also do your own research and bring it to your doctor for a discussion. “When researching, stick to websites that end in .org, .gov, and .edu,” advises Dr. Cash. Becoming clear on the facts is beneficial not just to you as an individual, but for the community as a whole.

Dr. Eric Betts

Family Physician

Dr. Courtney Cash

Family Physician, AFC Urgent Care - Ooltewah