Understanding Bipolar Disorders

It is an illness of extremes, of highs full of grandiosity and energy, of lows full of despair and lethargy.

It is an illness that is frequently not recognized as such, an illness that the National Institute for Mental Health estimates between five and six million Americans, approximately three percent of our population, suffer from.

One in five of those who experience this illness will choose to end their lives, 30 times the suicide rate of the general population. Indeed the mortality rate for untreated bipolar disorder is higher than for many types of heart disease and cancer. We cannot cure it. But we can treat bipolar disorder.

Symptoms and Cycles

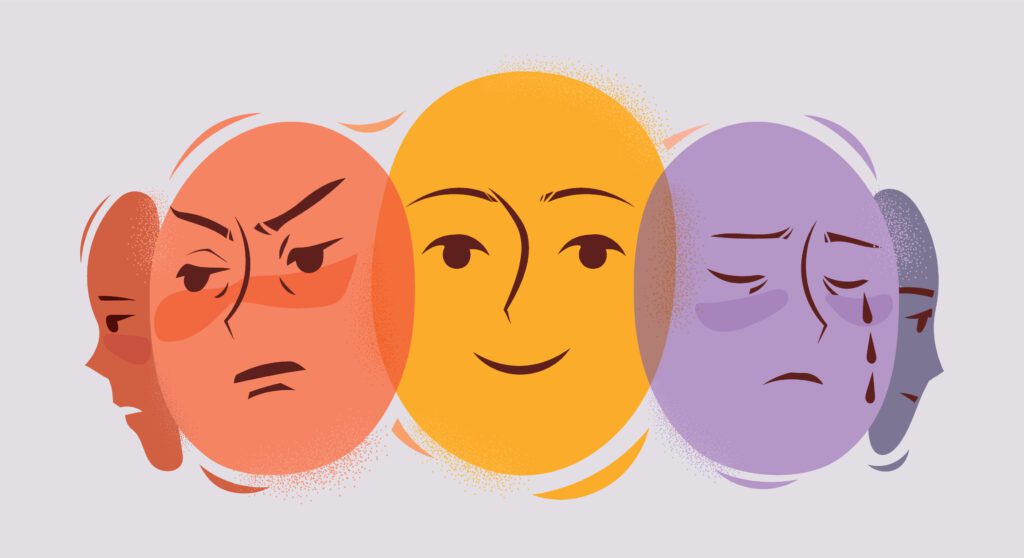

Imagine this: For a period of time you feel better than you’ve ever felt in your life. You have boundless energy, can exist on three hours of sleep a night, have so much to say you can hardly contain yourself, and can make life-changing decisions without hesitation. You might, or might not, notice that you are easily distracted, more irritable than usual, and that other people in your life think you are behaving foolishly. Given this close to euphoric state, why in the world would you think you needed help?

But then, more or less gradually, you begin to “come down” from your high. For a time you may behave normally, function well.

Sooner or later, however, you begin to have problems remembering, concentrating, or making decisions. You lose your appetite and find yourself sleeping markedly more or less than usual. You have no interest in activities you once enjoyed, and you feel hopeless, guilty, worthless. Your despair is so great you may contemplate suicide. Then again, if you’re fortunate, you may slowly emerge from your deep depression and enter another period of normalcy.

Most individuals with a bipolar disorder will repeat this cycle between two and six times a year. Mood changes are usually quite gradual with episodes of depression and/or mania, lasting from just a few weeks up to several years. (Children who develop this disorder may cycle between depression and mania several times a day.) Many bipolar individuals can be in a “normal” state for long stretches of time. During the first ten years of the illness, which is also the time period when the incidence of suicide is the highest, most bipolars will experience four to eight episodes of mania and/or depression.

The Causes of Bipolar Disorders

The problem is we just don’t know what causes bipolar disorder. Preliminary evidence points to an imbalance of brain chemicals which may cause interruptions in the normal way messages are carried between or within brain cells. PET scans show a distinct difference between the brains of individuals without bipolar disorder and those suffering from it. The brains of those with bipolar disorder have nearly 33 percent more brain cells that produce mood-altering chemicals than those without the disorder.

Genetic studies indicate that the predisposition to develop a bipolar disorder is inherited. Studies of identical twins have consistently found that if one identical twin is manic depressive, then the other twin is three times more likely than a fraternal twin to have a bipolar disorder. Kay Redfield Jamison in her book Touched with Fire (Free Press Paperbacks, 1993) examined the family histories of a number of artists diagnosed with bipolar disorders and found that, in almost every case, a parent or grandparent was also bipolar.

What we can conclude is that bipolar disorders are not a character flaw. They are indeed an illness that requires medical intervention. But do psychological factors play a role?

The answer is a definite maybe. Stressful life events seem to play a part in triggering the onset of some bipolar disorders. Loss of a job, a death in the family, a failure in school, or the birth of a child, for example, may trigger the initial onset of a bipolar disorder. We also know that once a bipolar illness develops, something as simple as a change in everyday routines seemingly can trigger the onset of a manic or depressive episode.

While we know that the typical age of onset of manic-depressive illness is late adolescence/early adulthood (although the disorder can occur at any age), what we can’t seem to find is a particular type of family history, parenting style, or pattern of abandonment or stress that are the typical precursors to the development of most emotional disorders. As Kimberly Bailey and Marcia Purse have written, “…if you are manic-depressive –what we now call bipolar– you were born with a bipolar time-bomb in your brain, and something in your life will set it off.”

And once you have it; you have it.

Treatment and Hope

The first symptoms of a bipolar disorder usually appear in late adolescence or early adulthood, and this illness strikes males and females equally. Left untreated, the illness will usually become more and more debilitating and disruptive. Unfortunately, there is no known cure.

There is, however, effective treatment, and it is important to note that many individuals with bipolar illness have and do lead productive lives. Consider just a few.

- Buzz Aldrin, astronaut

- Ludwig van Beethoven, musical performer and composer

- Hans Christen Anderson, author

- Charles Dickens, author

- Issac Newton, scientist

- Francis Ford Coppola, director

- Carrie Fisher, actress and author

- And the list could go on and on.

Lithium has been used for decades to stabilize the extreme mood wings of bipolar disorders. With properly monitored blood levels, lithium remains a relatively safe and effective, frequently prescribed medication.

Anticonvulsive medications such as Depakote were approved for the treatment of bipolar disorder by the FDA in 1995. Depakote has shown promising results as a mood-stabilizing medication. Newer medications such as Lamictal, Topomax, Neurotin, and Serequel may also prove effective. Antidepressant medications may be used in addition to mood stabilizers if the manic depressive individual is especially troubled by depression. Careful monitoring of the biploar individual’s reaction to antidepressant is crucial as they can, at times, trigger manic episodes.

As with any emotional disorder, what works for one individual may not work for another. The exact combination of medications used to treat bipolar disorder must be tailored to the individual. Once the right combination is discovered, many individuals with this illness can go on to lead relatively normal and productive lives, provided, of course, that they take their medications. And that can be, and often is, a problem.

Think about it. You’re feeling the best you’ve ever felt in your life. You have boundless energy, you see the world with great clarity, and your mind is solving problems and generating ideas at an unprecedented rate. Would you want to medicate yourself out of this state? On average, bipolars stop taking their medications an average of seven times before they decide, or can be convinced, to stay on them.

Bipolars have a tendency to use alcohol and drugs to regulate their mood swings, which, of course, complicates both treatment and compliance with treatment even more. Few people realize that Carrie Fisher, the Princess Lea of Star Wars fame, used illegal drugs and alcohol to try and control her bipolar disorder throughout the filming of these movies. Only years later when she finally accepted the reality of her illness and became a spokesperson for individuals with bipolar disorders did she seek and receive proper medication and treatment.

Turning to self medication makes sense. During the mixed phase of the disorder, when the bipolar individual is simultaneously experiencing both depression and agitation, or during the depressed phase, the individual is so uncomfortable that he or she will turn to anything offering relief. Historically, alcohol has been the self medication of choice. Indeed, the incidence of alcoholism among bipolars is very high. So treatment is often complicated by the fact that the bipolar also has a substance abuse problem, which, it turns out, seems more acceptable to them than having a mental illness. Thus the substance abuse may get treated, but the underlying bipolar disorder does not.

Psychotherapy

As a therapist, I know that there is a limited, but not insignificant, amount of help I can offer a bipolar patient. What I can do is this:

I can educate the bipolar individual about the nature of his or her disorder. This psychoeducational, as well as any other, intervention works best when the bipolar patient is in a relatively “normal” period, neither manic nor severely depressed. I can help these individuals understand that they have an illness, through no fault of their own, that we cannot cure, but that we can effectively treat. I can help them recognize the early warning signs of a relapse and encourage them to see their attending psychiatrist immediately. I may be able to use elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy to help them replace negative, self-defeating thought patterns and behaviors with positive, effective ones. I may be able to help them to minimize conflicts and stresses that can upset their daily routines and emotional stability.

I can point out to them that without treatment, their condition will worsen. Their episodes of mania and depression will become more severe, and they will most likely cycle into these episodes more frequently. Often it is helpful to encourage bipolar individuals to keep a daily record or diary that helps them keep track of their moods, personal goals, and treatment plans. A number of online sites sponsored by drug companies have interactive diaries that can be quite helpful to bipolar individuals. One such site is sponsored by Asta Zeneca.

Importantly, I can work with the families of these individuals to help them help their bipolar member and to support them in dealing with this most difficult illness. I can help the family realize that they did not cause this disorder, nor is this a character flaw or weakness in the individual who has it. And I can help the family realize that there are a few things they can do that may help.

For example, I can encourage the family to maintain a predictable routine, to provide structure. Bipolar individuals seem to do best when their life is predictable. I can also point out to the family that boundaries are important. Specifically, the family does not need to tolerate verbal or physical abuse. Family members can be there for the bipolar family member, they can be supportive, and they can listen and encourage, but they should not tolerate inappropriate behavior. Keep in mind that if the bipolar individual chooses not to get help, there is little you can do. If their behavior is not tolerable, you may have to hospitalize them. If they do become threatening to themselves or others, a 911 call must be made. What you don’t want to do is become permissive or co-dependent.

Families can also profit by joining a local support group or an on-line group. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the Mayo Clinic, among others, provide information and updates about bipolar disorders. I can and do encourage family members and/or relatives of the bipolar individual to seek support and to take care of themselves.

Suicide

We tend to associate suicide with depression. Bipolar individuals, however, are more likely to take their own lives when they are in the unbearably painful mixed state, when their depression is energized by anxiety and agitation. Bipolars may well feel that there is no way out of their pain. Remember, if left untreated, bipolar individuals are likely to experience more frequent and more severe mood swings, which become increasingly painful to them.

Contrary to popular belief, individuals who commit suicide do let others know of their intentions. Research suggests that fully two-thirds of bipolar individuals who commit suicide clearly communicated their intention to do so. We need to heed their warnings.

In Conclusion

Often misdiagnosed or masked by alcohol or substance abuse, bipolar disorders are extremely serious, and not infrequently, fatal. We cannot cure them, but we can successfully control their extremes, allowing individuals with these disorders to lead productive lives. We need to work harder to remove the stigma of this and all mental illnesses, to diagnosis them earlier, and to encourage their victims to seek help sooner. We still lose too many to bipolar disorders.